“It’s like standing at the edge of a cliff, and they keep jumping off the cliff, and I keep pulling them up. No matter how many times I pull them back up or beg them not to jump, they just keep jumping. I know I need to let go of the rope, but I don’t know how to do it. I’m so scared.” I remember sharing this metaphor with a friend as we talked about our experience loving someone with an addiction. The tight grip on the rope felt like the only thing we could control, the only connection we could maintain with our addicted loved one. Letting go of the rope could have serious consequences for our loved ones, consequences we may have spent months or years or decades helping our loved one keep at bay. How could it be a good thing to let go if it meant our loved one could finally come face-to-face with those consequences we had worked so hard to protect them, and ourselves, from?

The first time I considered loosening my grip on that rope was when I was introduced to the Karpman drama triangle.

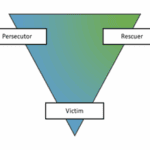

The drama triangle is a concept that Psychiatrist Stephen B Karpman created to depict three roles people play in relationships that keep them stuck in drama and dysfunction. While these roles of dysfunction can pop up in any relationship, I have noticed they are particularly applicable in relationships where there is addiction.

First there is the persecutor. When someone is playing this role, they are the bully. This role is characterized by behaviors like criticizing, attacking, blaming, and shaming. Next is the rescuer. The rescuer is known for solving problems, controlling the situation, manipulating – they appear self-sacrificing, but in reality, they do not trust the other person’s ability to help themselves. The last role is the victim. When we are in this role, we don’t value ourselves and often defer to others. The victim is helpless, needy, complaining, and blaming.

While people often tend towards one specific role, when we are in the drama triangle, we often dance between roles. Here is an example of a mother and her adult child who is struggling with an addiction: The child is unable to pay rent and explains to the parent that it is not their fault because their tire went flat and they had to use the money on that so they could get to work (victim). Although the parent knows their child spent the money on their addiction, the parent feels bad and pays the child’s rent (rescuer). The next month, the child reaches out again, needing help with rent. This time, the parent might be fed up and become aggressive, blaming and shaming (persecutor), or they may turn into the victim, “I can’t say no to my child.” In the drama triangle, instead of taking responsibility for ourselves and what we do have control over, our energy is focused on the other person.

As I learned about the drama triangle, I realized I had played every one of those roles, as had my loved one. We were spinning around the triangle, trapped in the same old song and dance. And it was keeping us stuck. My loved one was stuck in their addiction, and I was stuck in my codependency. I knew it was time to loosen my grip.

As a licensed counselor, it is my job and my privilege to walk with people facing the dilemma of whether or not to drop the rope. Letting go is not an easy task, but it may allow our loved one to finally pick up their own rope. Next month we will explore The Empowerment Dynamic, which holds the key to changing the cycle and finding peace even amidst our loved ones struggle.

Cassie Greene, MA, LAC, AZ Counseling Collective, Cassie feels called to help others walk through the challenge of loving someone with an addiction.

This was very helpful to me and I look forward to reading next months article. Thank you so much.